Uncovering Shakespeare’s Community Impact

When I arrived at the Huntington Library on the third of April 2019, I was searching for details to include in my dissertation, Grassroots Shakespeare, on amateur Shakespeare performance in the United States.

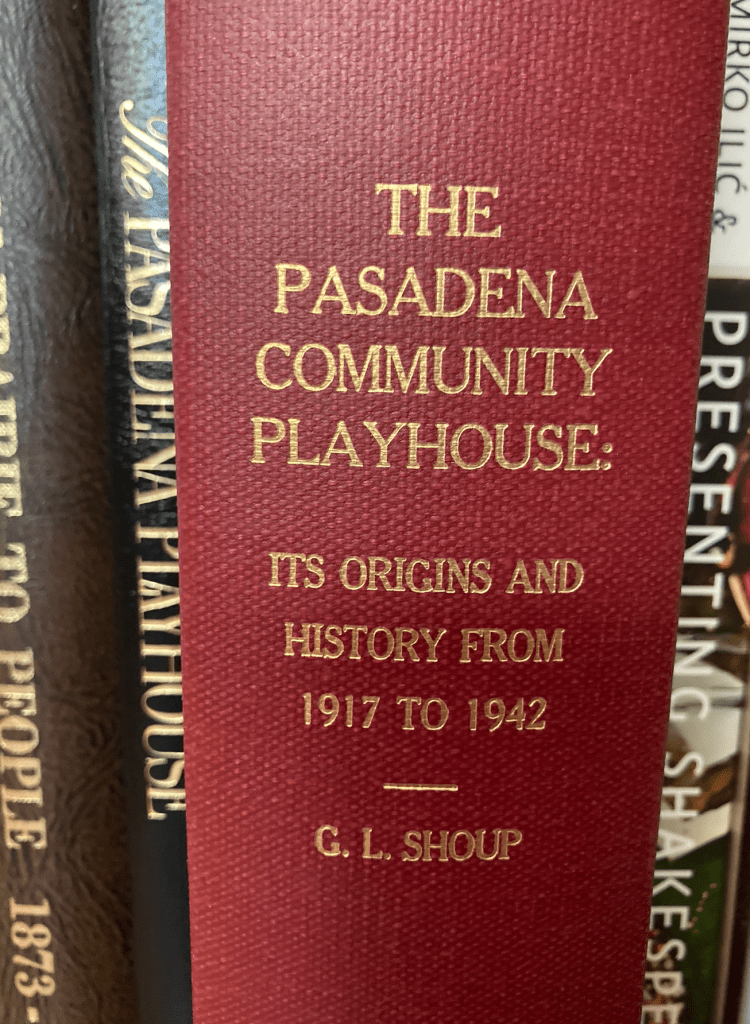

Specifically, I was trying to investigate the background of the Pasadena Community Playhouse so I could understand their success with community-based Shakespeare performance. I determined that I would find some answers in a 1968 UCLA doctoral dissertation by Gail Leo Shoup entitled The Pasadena Community Playhouse: Its Origins and History from 1917 to 1942.

I had established that Pasadena Playhouse Founder Gilmor Brown (1886-1960) had led the first effort to produce all of Shakespeare’s plays in the United States. How he achieved this with an all-amateur cast needed more context to help me prove my overall thesis, as it went against previous scholarly narratives that the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF) in Ashland, Oregon, in 1935, was the first Shakespeare Festival in the United States. Nevertheless, OSF certainly is the longest-running, but it was not the first.

However, I had trouble finding this dissertation. The Pasadena Public Library’s copy had vanished from the shelves, and so had the copy in the Los Angeles Public Library. I had one more option: UCLA’s library, but there was an odd fee associated with tracking it down.

Then, another search yielded one more possibility: the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, the institution that houses many of the Pasadena Playhouse’s early records. The Huntington describes its archives as “one of the world’s great independent research libraries, with some 12 million items spanning the 11th to the 21st centuries.” As I schemed my next trip, I wondered why no one ever told me that researching could be this much fun.

I submitted my application to be a reader at the Huntington and secured my timeslot to pick up my name badge and receive a briefing on how to utilize the collection. My requested item, Shoup’s The Pasadena Community Playhouse, was brought to me. I collected myself and sat down in the elegant reading room. After two weeks of searching for this dissertation, which was surprisingly large, I gripped it anxiously. I paged through it, turning each page as if I would discover a groundbreaking link between two disparate areas of my research. Then, as I paged through the volume, I read the following:

“Kingsley was the scene of his first major pageant in June, 1912, when he gave A Midsummer Nigth’s Dream on a riverbank, with cottonwood trees as a backdrop. For over three weeks he trained a cast of almost one hundred.” – G L Shoup, The Pasadena Community Playhouse

This brief passage provided me with numerous leads for further research. I had many questions to answer; just to name a few:

| 1) If Gilmor Brown had become the first person to produce all of Shakespeare’s plays in America, how did his work in “Kingsley” prepare him for that? | 2) How did Gilmor Brown amass one hundred local actors from a small Kansas town without any organizational infrastructure? | 3) Why wasn’t such a large production part of historical narratives about Shakespeare performance in the United States? Why was this production lost to history? |

As I began to comb through historical records, I discovered surprising twists immediately. 1) The town in question was, in fact, “Kinsley,” not the “Kingsley”, and 2) Gilmor Brown did not produce this community enterprise alone. These omissions are hardly the fault of Shoup, whose scholarship on the Playhouse is quintessential. Accordingly, I would later learn that Shoup’s primary source for his brief discussion on Kinsley came from Brown himself, who went out of his way to ensure the Kinsley festival’s unmentioned co-founder faded from history. My recent scholarship recovers the story of the festival’s other founder, Charles “Charlie” Rufus Edwards.

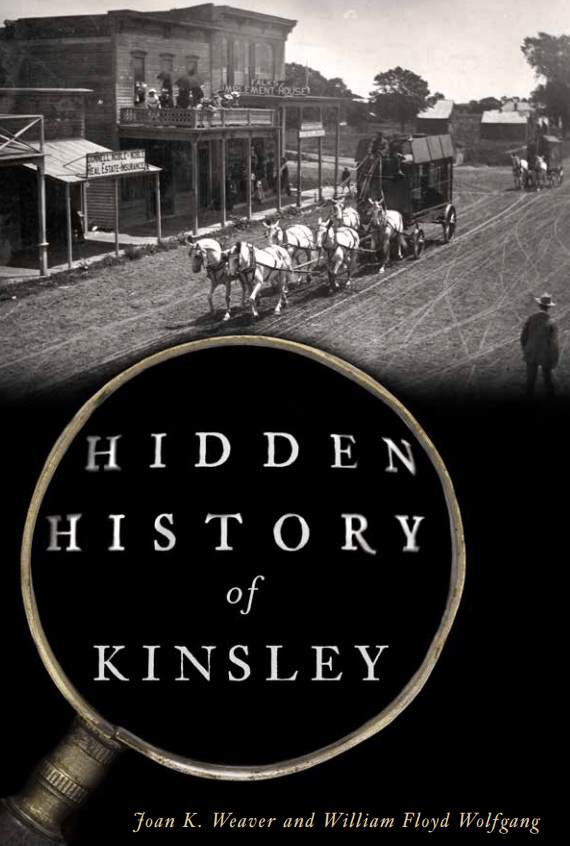

In upcoming entries, I will share parts of Charlie’s story and how he became a leader in the early community-based theatre movements in the United States. These posts will lead up to the release of our Hidden History of Kinsley (History Press 2025), and eventually to my Fairies in the Short Grass: Visions of a Small Town Shakespearean.

Leave a comment